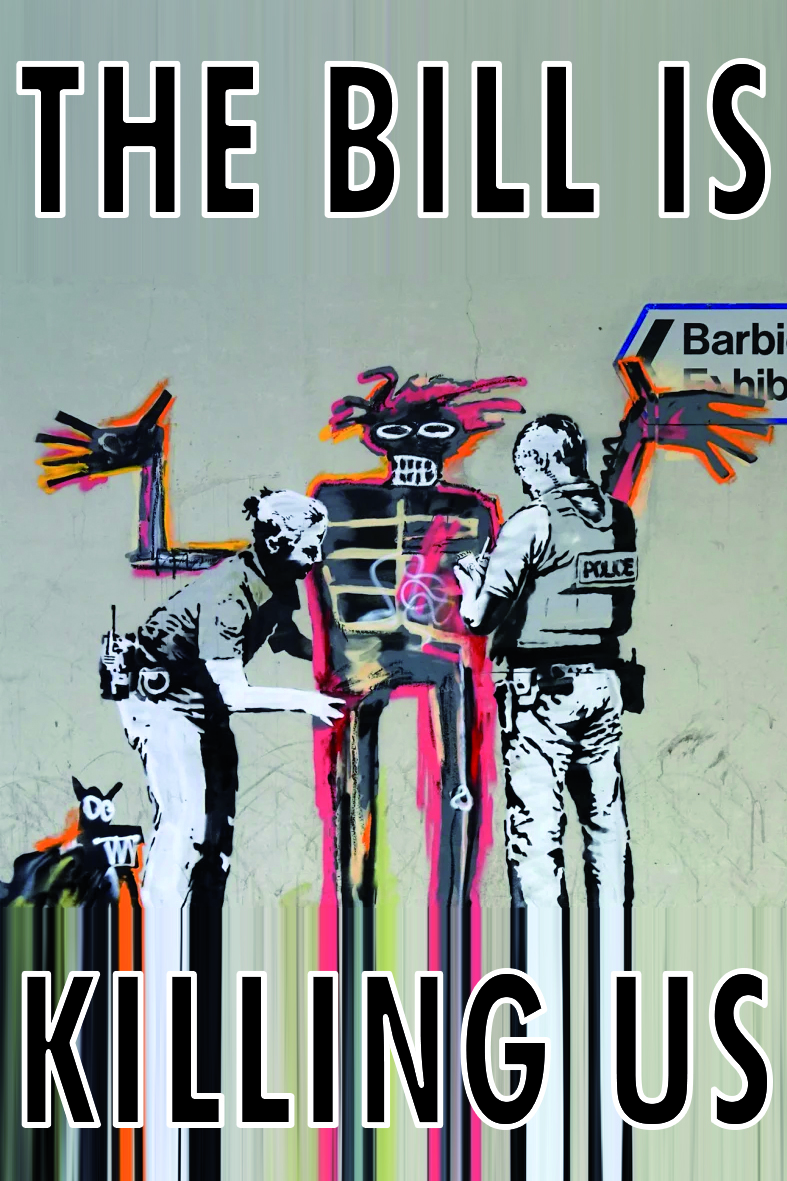

The Police, Crime Sentencing, and Courts Bill is rapidly approaching and holds major implications for black and brown communities across the UK. As the Institute of Race Relations said way back in March of this year, “the race and class implications are massive and go beyond the right to protest”

To get an understanding of what the future holds for our communities, we only need to look back at history. Just recently, I visited the outstanding War Inna Babylon, at the London ICA. As moving and powerful as the exhibition is, what it conveys is not only a community’s fight for truth and justice in the wake of police brutality and deaths in custody, but of the continual resistance to racist and autocratic policing over the decades.

Author and Professor of Sociology, Alex Vitale, once said that “the police are not here to protect you”, and as people of colour, we know this to be a truth. Over the past two-to-three years, there has been an increase in the disproportionate use of stop and search nationwide. Here in Avon and Somerset, we have seen a reintroduction of Section 60 powers, and during lockdown, black people became a frequent target for fines and increasingly disproportionate and racist policing.

As a police-monitoring organisation, we noted the 38% increase in the use of stop and search powers across Avon and Somerset (2019 to 2020 respectively), and the stark fact that black people became 6.4 times more likely to be stopped than their white counterparts in the county. We also expressed a great deal of concern that not only did the police not acknowledge this fact, but in fact outright denied its existence, whilst drawing on the reactionary “more whites are stopped than blacks” trope.

Of course, this was not only infuriating, but troubling for many of us. The lack of trust and public confidence in the police has become increasingly evident over the past eighteen months or so. Rather than bridge the rapidly emerging divide that exists between themselves and communities, they seem more inclined to contain than protect. We are currently witnessing an increasingly aggressive and militarized response to crime that has adopted the authoritarian ‘law and order iron fist’ approach of the conservative leadership of this country with relish.

We need look no further than the introduction of Serious Violence Reduction Orders (SVRO) to understand the implications. In the Conservative party 2019 pre-election manifesto, it was stated that “police will be empowered by a new court order to target known knife carriers, making it easier for officers to stop and search those convicted of knife crime.” However, the landscape was soon to change when re-elected home secretary Priti Patel issued a consultation document, proposing that anyone aged 18 or over, who is convicted of an offence involving a knife or other offensive weapon, could also be subjected to an SVRO stop.

We need only look at the legal definition of offensive weapon (‘any tool made, adapted or intended for the purpose of inflicting mental or physical injury upon another person’) to understand that the scope and target range of SVRO powers increases dramatically on this basis, as does the potential for disproportionate stop and search. The issue we face is that it has always been unlawful for a police officer to target someone based on previous criminal history. To do so allows no propensity for people to rehabilitate and change, and effectively allows the law to punish us forever.

Of course, what the law states the police should and shouldn’t do and what they actually do are very different things. As a ‘mixed race black male’ (my PNC record definition), I have been stopped and searched over 50 times in my life. Upholding the ‘once a criminal, always a criminal’ narrative does not bridge divides or heal wounds and regain trust in the police. It creates trauma. It creates cycles and dog whistles to the reactionary elements of society, as well as within the police themselves. By increasing the scope of powers that are frequently abused, we are moving rapidly away from “policing by consent”, and towards a model of policing from a bygone era.

As IRR stated in March, “policing in the Brexit state” is a trip back in time to the 1980s. Recently, the government said that discrimination against black people and travellers and the impact on us from the bill is “objectively justified”. They went further to state that “any indirect difference on treatment on the grounds of race is anticipated to be potentially positive and objectively justified as a proportionate means of achieving our legitimate aim of reducing serious violence and preventing crime.”

This statement has massive implications for our communities and what the future of policing in the United Kingdom means for us. It’s clear that, to some in the echelons of power, the ends justify the means. That racial profiling, stereotyping, and disproportionate targeting of anyone who is deemed to be a potential criminal, often seems to be based on race alone, is quite simply collateral damage.

At present, black people are nine times more likely to be stopped by the police in England and Wales than our white counterparts. The police seem happy to open the doors to racist strategy without any consideration for those who are on the sharp end of such powers. Stop and search has failed spectacularly to act as an effective deterrent to knife crime, and an expansion of these powers will only continue to destroy public confidence in policing.

I share the same concerns as the Criminal Justice Alliance Group, that we are looking at the disruption of the lives of those who are rehabilitating in our communities and, from my point of view, no doubt ‘discretionary’ ongoing vendettas by malicious racists, who should never have been granted a position of authority. In late 2020, the ex-Met Police Superintendent Leroy Logan said, “Young people feel they are over-policed and under-protected. They see the police as predators.”

Speak to anyone in St Pauls or Easton in Bristol, and you’ll notice the general mistrust and disillusionment with the police. Communities here, like those in London, have a long and volatile relationship with the police, and, with the upcoming PCSC bill, we can only expect things to become increasingly worse before they become better.

The focus on the bill, in particular, the goal of Kill the Bill protests, has primarily been to raise awareness about the attack on our civil liberties and the right to assembly. Of course, like many others, I completely agree that protest is a cornerstone of our democracy. The fight is, without a shadow of a doubt, an important one.

However, it’s absolutely worth noting that other than a large amount of righteous noise being made about the impact the bill is going to have on travellers’ rights, it seems that along the way, the primarily-white Kill the Bill protest movement seems to have forgotten about us.

Don’t get me wrong, the brutality of Avon and Somerset police during the protests earlier this year has been unforgiveable and has produced some of the most disgusting displays of state violence I have ever witnessed in my life. It’s worth remembering that when the uprising occurred at Bridewell that weekend in March, following the first Kill the Bill protest, a black man with a heart condition was tasered three times and violently assaulted by an armed response team in St Weyberg.

When you understand that the horrific levels of violence seen and used against peaceful protestors is used against black and brown communities far too frequently, you realise that the police commit hate crimes against us every day. At points, I’ve cringed seeing the, dare I say it, middle-class trendy student “send flowers to Brixton police station please!” XR protestors take centre stage, who think living in St Pauls is “edgy” and drinking in Easton is getting back to their nan’s roots, but you know what? It’s their fight, too. Except when they walk past a stop and search that seems a little rough, because it’s not their problem.

The support work I have been involved with, as a case worker and a member of Bristol Copwatch over the past 12 to 18 months, has been emotional. When we’ve seen unjust convictions overturned for those we have been supporting, it’s been liberating. When I’ve been called an everyday hero, it’s touched my heart. It’s made me revisit my own trauma the police have created, from years of stop and search harassment and, most recently, low key surveillance, tails, and ongoing harassment, because of the work I do in the community.

From what I’ve seen whilst volunteering, and what I know about the police as a whole, it is clear that they are unlikely to change their approach towards marginalised communities. What they put us through reflects the corrupt system they enforce. It mirrors the attitudes of those in the highest echelons of power, and it’s something that we as people of colour should always stand together and resist.

John Pegram, Bristol Copwatch founder and case worker

________

Thank you to John for the article, follow him and the rest of the team via @BristolCopwatch.