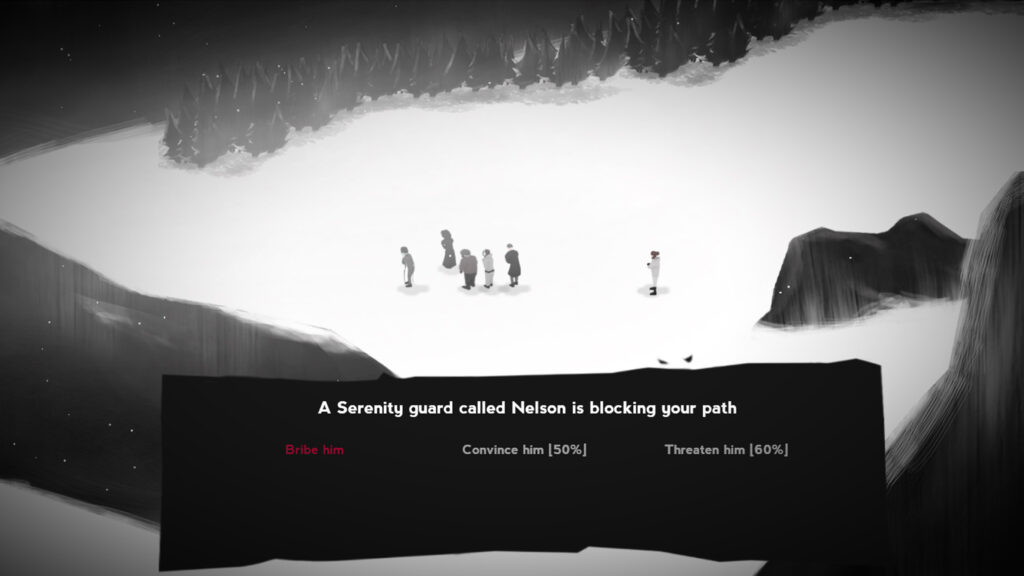

The Man Came Around is a game of complex moral decisions, where you attempt to navigate across a militarised border with a group of people fleeing an authoritarian regime. Organise sat down with its developer, Thierry, to talk about indie game creation, the game, and the all-too-real politics and events that inspired it.

Thierry: Making games is something that I always wanted to do since I was a teenager but, at the time, being a game developer wasn’t on the cards, it was less accessible. So I went to university, but after that I found there were formal lessons on it, my dream was really possible, so I jumped in. This is the thing that I wanted to do for so long, I thought, ‘Oh, it’s not going to be that difficult.’ I had no idea how hard it would be.

What was it that surprised you with the difficulty?

Thierry: I mean, some difficulties were understandable. I had no programming background, so learning to code was… a process to say the least. I also had no artistic background, so that was another anticipated struggle. The thing you never think about though, as an indie solo developer, is all the other stuff that goes with creating a game: the time management, the marketing, the financial management, grant applications, running a crowdfunder, setting up a business. You think, oh, I’m just going to develop a game and it’s going to be great. But all those things add up and then you need to be proficient at a lot of stuff that you didn’t consider at first.

I also made another very common mistake, thinking that my game was not going to take that long! In my case, it took seven years to do it. For a couple of years, I was just learning and of course these last years weren’t easy for anyone, which slowed things down. Also, being a solo developer, if anything happens to you, if you get sick, or burnt out, it really slows things down.

Seven years is a big chunk of time. How did you manage to support yourself while you were working on it?

Thierry: Many different ways. First off, my family helped me and I like to be honest about that. I think a lot of times people don’t really understand how the financing works and having money upfront makes a big difference, so getting help from family, friends, and fools, is a way to do it.

Alongside that, I did freelancing, teaching kids to code, and set up a crowd funder. I also got support from a regional state institution in Belgium - they have some game funds you can apply to get loans or grants. When you start, you will think how it’s going to be right, but finding funds is important if you like to pay your rent and being able to eat. And it’s also a skill because you’re going to have to do funding requests and a lot of paperwork that you never thought you would do.

With all of that, would you recommend anyone else tries to become a solo developer?

Thierry: That’s a tough question. I wouldn’t discourage anyone, but it’s going to be a hard task. People need to realise that there is a lot of consideration about finances. A lot of projects never finish just because the devs run out of money to support themselves. You really need to ask yourself what is my Plan B, my Plan C? What are you going to do if the project is delayed? If things you hope to rely on don’t pan out, it can be very hard. But it is also very rewarding making a game. If you really want to, you should try it, but be careful how you plan.

To get more specific, what was it that inspired you to make this game? Why did you decide to make The Man Came Around?

Thierry: At first, I just had a vague idea that I wanted to do a game with impactful moral choices. Then I decided it should be a survival game. At first, I planned to do the classic story, a plane crash in a mountain, will someone eat someone, those kind of things. After a while, the idea was a bit too tropey and boring. Then, in 2016, just over the border from me in France, there were these huge riots.

They were protesting against labour reforms. I don’t remember the specifics now, but there were demonstrations all across France, and the French police were just beating everyone. I thought, when you look at France, that country always seems so close to becoming authoritarian. It seems when people complain, the only way the French state reacts is to send in riot cops.

At the same time, there was the Syrian refugee crisis. Europe was putting up barbed wire to try to stop refugees in places like Hungary. You already had a lot of places in Europe with walls and fences and guards, but this was a further escalation. I hated the way these people were being treated.

Those two things were what inspired the idea for the story. The story began to form. The basic idea was how would we react if we had to do the same thing for any reason, to have to leave your country and to go in exile. So that’s how the best idea came by.

So your thought was ‘What would it be like if people in a Western European country had to do the same thing as those in Syria, and flee their homes?’

Thierry: Yes, if we had to leave. For me, considering the direction Europe is going in, one of the likely reasons would be to flee an authoritarian regime. Then there was the irony of it, being kept in by the fences we’d built to keep others out, having to flee to the countries we had previously shit on. Of course, after I’d started, you had the US election and all Trump’s escalating rhetoric about the wall, and banning migrants. It mirrored a lot of what I had already been writing.

What other real-world politics fed into your game over the years?

Thierry: There are many examples. It’s a common story, a social protest of people not being heard by a government, and the same response from the government every time: repression, repression, repression. We saw it with the Black Lives Matter movement in the US, with further protests in France, with climate marches. They are different, but there is always the setup of people asking for something reasonable, like not killing the planet or having a living wage, but there is no dialogue entered into by those in power. Just we’re going to beat you up, just enough to discourage you, tire you out, manage the discontent, until you have to give up and go back to work, and face the softer repression.

So I began thinking of how we could get past that. In the game, the country is on the verge of something, with many social movements pushing together. The government is on the back foot, so their reaction is to go harder with the repression, to double down, which I think is a real possibility in the real world.

One thing that caught my attention when playing, was that you had the committed paramilitary police force, but also the private security there for a wage. It was chilling, reading some of the snippets of dialogue they had, justifying their actions. Definite echoes of things you’ll see when on social media or the news, justifying repression.

Thierry: Yeah, they are able to manufacture consent for their repression. In our society there are always people in favour of the state, no matter what. They want stability and order, or they just don’t care.

The border control in the game is privatised, as more and more things in the real world are, for cost, profit, and lack of accountability. I wanted the guards to represent the kind of right-wing mindset you might hear play out at two in the morning at a pub, repeating the kind of prejudiced statements you see everywhere.

I wanted to show how easy it is to justify things, to fall into being part of the repression because you feel like you have some kind of control, to feel empowered even though you are just a minimum wage tool of the state.

As well as the terrifying prospect of reality, were you influenced by any games or other media?

Thierry: I think one of the big ones is This World of Mine. It’s also a black-and-white game about people surviving in a war, and it’s also a good example of moral choice, having an impact on the characters afterwards. There was also another game that’s called Gods Will be Watching. Part of my game is definitely inspired by that.

When you were working on it, did you have in mind who would play it or who it would be for?

Thierry: Not really. I knew that people that would enjoy it would be a short list. Partly because of its strong political message, which would exclude right-wingers, and partly because it would only appeal to people who like the more indie games experiences.

At the start, I hoped to change people’s minds perhaps, but I don’t expect people to have a big change of heart because they play the game. It became more like an outlet for me to express stuff or my discomfort towards how society is going.

Of course, if someone plays it and it makes them think about the way things are going and reframe stuff in a new way, I would be more than happy. It’s just that I’m not counting on it too much. Media is one part of a lot of stuff that you can do to change the world, and at the end of the day I’m like, okay, it’s kind of just a game.

There is more important stuff you can do to convince people to change their political views, but that’s what I had at the time. That’s what I could do. So I put my effort into that.

I don’t expect someone’s going to play any one game or watch any one movie and then suddenly be like, oh, you know what? I need to bring down the government. But taken as a whole, media like this can have a big effect. Otherwise, you wouldn’t get organisations like the US military sponsoring movies and gaming events.

Thierry: It’s true that if you can have access to a more diverse messaging, and media that presents a different kind of opinions, it really helps. Does it help more than activists on the ground? No, it doesn’t. But I really also understand that the more you get exposed to a message, the more you can get receptive to it.

We do need more diversity in the kind of discourse and representation in games. I spent a lot of time with other indie devs, so I’m in a bit of a bubble and sometimes I forget how standardised a lot of big games can be in their endorsing of status quo propaganda.

I hope for games to have way more diversity in the stories they tell. It’s always cool to have more progressive games where presentation and mechanics are important, but so is the message. Indie games can afford to take risks with this, in the way big-budget studios are often prevented from doing.

Talking of presentation, you said you didn’t have any sort of an artistic background, so how did you create your game’s striking art style?

Thierry: Right at the start of the project, there were two of us, but the other guy had to stop because the development was hard at the time. We’d decided black-and-white due to the mountain setting. When it came time to redo the art myself, I stuck with that, partly because I thought it would be easier than colour. I got freelancers to do line art for the characters, but did the rest of the art myself. Working with limitations can be good. I knew it was never going to be a colourful and super-detailed looking game, but it doesn’t have to be. I embraced the rough minimalist style, because it fit the story.

I always think as long as an art style is striking, I prefer simpler styles, but ones you can recognise. If you play Papers, Please, you’re going to recognise it right away. Is it the most beautiful in a traditional sense? No. But for me, it works perfectly, and you couldn’t confuse it with any other game.

Okay. And what do you see as being next for you? Now you’ve got your game out.

Thierry: I’m not sure yet if I’ll be able to, but I would like to continue making games. Maybe grow the studio. Developing mostly solo was an interesting experience, but I’d like to do a game with others. Whatever I create, I want it to have a message, and to keep complex moral choices. I think it’s one of the most interesting things about video games is that it’s interactive, so you can have an action and seeing the consequences of that action, which you wouldn’t get from a movie or from a book.

My final message to any gamers would be to support indie games, try them out, as you will definitely find some gems.

- - - - - - -

The Man Came Around is out now on Steam for Windows and Mac. It comes highly recommended by us at Organise!